PM Magazine: Restoring Elegance

The rehabilitated Charter House in Princeton remains true to its historic character. October 2008

If the walls of this old house could talk, what incredible tales they could tell. From its humble beginnings as the home of a Prospect Avenue printer, to its expansion and stately reincarnation as one of Princeton University’s elite eating clubs, the Charter House over the past 116 years has survived much, beginning with a cross-town move to Cleveland Lane and a devastating fire. It has served as the home of authors, heiresses, powerful newspaper publishers and Grammy award winning singers.

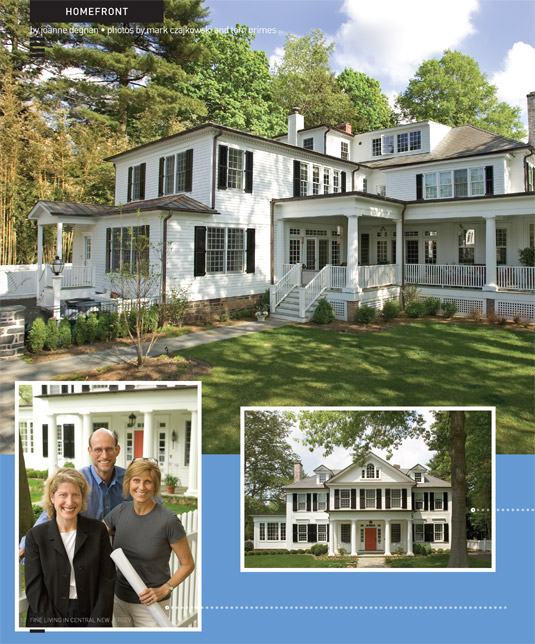

One of five houses to be featured on the Historical Society of Princeton’s Historic House Tour Nov. 8, the Charter House has recently undergone an extensive restoration aimed at transforming the chopped-up interior space, reflective of its university eating club origins in the early 1900s, to a more open floor plan where a modern family with three young children could live comfortably. “We look for compelling, interesting houses for the tour that people will enjoy going to see,” says Barbara Webb, the society’s director of development. “This home has undergone a lovely rehabilitation, and it does have historical significance as well.”

The oldest part of the Charter House was built in 1892 by a printer named W.C.C. Zapf, according to Wanda Gunning, a longtime trustee of the historical society. In 1903, Princeton University’s Charter Club purchased the clapboard house and two adjoining lots so that the structure could be expanded and transformed into a stately Georgian Revival clubhouse with a grand entrance portico and four two-story Doric columns. These massive columns, and the five identical dormers above them on the third floor, didn’t survive the structure’s move to Cleveland Lane in 1912 and a subsequent fire there.

The current homeowners, Emily and Johan, who asked that their last names not be used, bought the three-story house in 2000 knowing that renovations were needed. The roof and third-floor ceiling were bowed in one section, and they disliked how the front door opened into the living room in a way that prevented furniture from being placed by the fireplace. The long narrow kitchen and family room at the back of the house were segregated with walls and separate doors. The rest of the house presented an awkward layout with its labyrinth of doors, hallways and small sitting rooms that had to be crossed to get to an adjoining room.

“Every time people would come over they’d say, ‘Your house has so many doors I keep getting lost,’” Emily says. “It made the house really confusing because you were just opening and closing doors all the time to get to the same place.”

Princeton architect Marc Brahaney, of Lasley Brahaney Architecture and Construction, says his task at 33 Cleveland Lane was an “adaptive” restoration. The fire had destroyed much of the interior’s turn-of-the-century woodwork and other period details making a historically accurate renovation difficult. In the nine decades since the fire, other changes had also been made by subsequent homeowners. (Some former residents include the writer Hugh MacNair Kahler; an heiress to the multi-million dollar Lydia Pinkum women’s elixir fortune during the 1920s; newspaper publisher James Kerney in the 1950s; and country singer Mary Chapin Carter, who grew up in the house during the 1960s.)

Janet Lasley and Marc Brahaney in the roomy kitchen

“What was there to work with and salvage we did,” Mr. Brahaney says. “Otherwise, we had to be adaptive to what Emily and Johan needed as a family.”

Ann Marciano, marketing manager for Lasley Brahaney Architecture and Construction, looks out the front door of the home's foyer (photos by Mark Czajkowski).

Ann Marciano, marketing manager for Lasley Brahaney Architecture and Construction, looks out the front door of the home's foyer (photos by Mark Czajkowski).

The result was a renovation that maintained a traditional look outside, reconfigured interior rooms, and added only about 800 square feet in new space over three floors. A small covered porch and foyer were added to the front of the home so that the entrance vestibule no longer intruded into the living room. The narrow side-by-side kitchen and family rooms were changed to a more open front-to-back arrangement, minus the walls and doors that divided them before. A generously sized mudroom/laundry room was added with soapstone counters and cherry cabinetry that provide ample storage space.

In the backyard, the dilapidated three-car detached garage was redesigned and rebuilt to include a second-floor exercise room and a bathroom for the nearby pool. A small rectangular covered porch behind the dining room was expanded into an L-shape so that it could be accessed from the kitchen, dining room and the sunroom. “We used the outdoor porch as an element to join the indoor spaces,” Mr. Brahaney says. “We tied it all together and that made the back of the house much more attractive.”

Upstairs on the second floor, the pass-through sitting room with doors to two adjoining bedrooms was transformed into a children’s playroom with hand-painted wall murals and a hand-painted border on the hardwood floor. The third-floor staircase, which had been fully enclosed behind still another door that blocked much of the secondfloor hallway, was moved to make room for a new master bathroom. The third floor, which had been left unfinished as attic space after the fire, was finished to create a home office and a full bathroom.

The children's playroom features hand-painted wall murals and a hand-painted border on the hardwood floor (photo by Tom Grimes).

Throughout the house, interior designer Tara Dennison, of Dennison and Dampier in Princeton, seamlessly mixed in new furniture pieces with the antiques the couple had been given from relatives in Belgium and Switzerland. A shopping trip that Emily and Ms. Dennison took to London led to the discovery of the Scalamandre House fabric, a raised velvet on a cream silk in a 19th century French design, that was used to reupholster the heirloom chairs in the living room.

The homeowners decided against rebuilding the Charter House’s five original third-floor dormers and massive two-story Doric columns that it had on Prospect Avenue. Recreating the original top-heavy look would have made the house seem too overpowering on its current halfacre lot, Emily says.

A three-car detached gargage was redesigned and rebuilt to inlude an excercise room and bathroom for the nearby pool (photo by Tom Grimes).

“We didn’t do a historical restoration in the sense of recreating what the original was or meticulously replicating what had been here,” Mr. Brahaney says. However, “we feel we were true to the historic character of what this place was and gave it back its elegance.”

The Historical Society of Princeton’s Historic House Tour, featuring the Charter House, among others, will take place Nov. 8, 10 a.m-4 p.m.

Tickets cost $35, $30 members. princetonhistory.org